Netflix’s latest sci-fi series, 3 Body Problem, is an epic tale with a huge cast of characters spanning a vast number of locations, time periods, and even dimensions. And the editing and post-production of the show was almost as complex.

Four editors (Simon Smith, ACE; Katie Weiland, ACE; Anna Hauger, ACE; and Michael Ruscio, ACE) battled it out over a two-year period to bring the vision of the series’ three showrunners, David Benioff and D. B. Weiss (Game of Thrones) and Alexander Woo (Star Wars: The Clone Wars), to the screen.

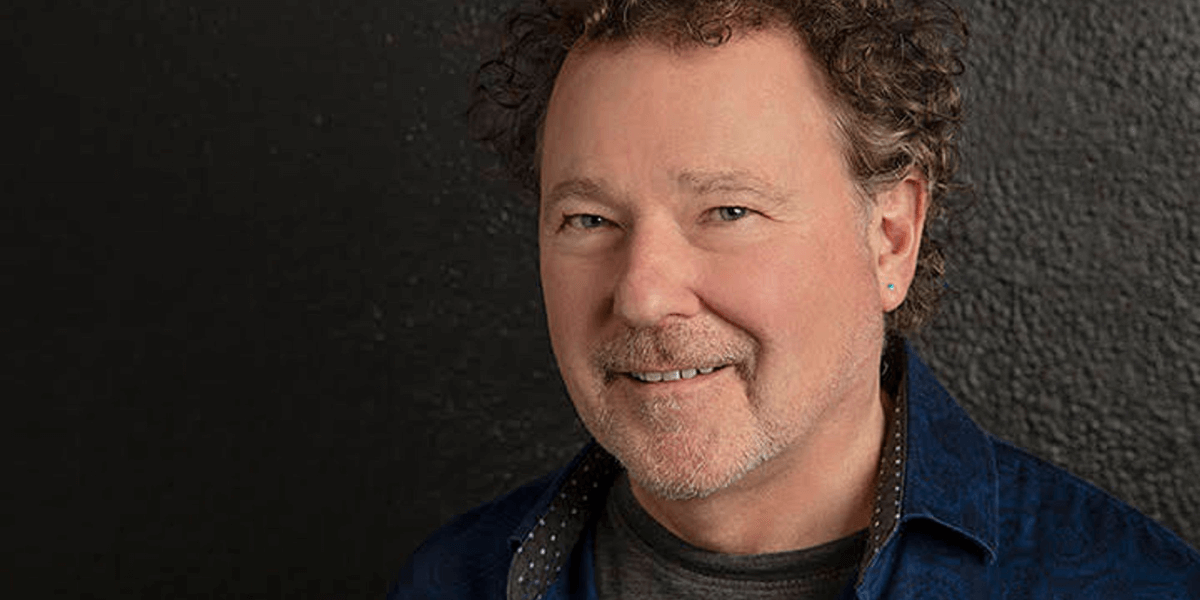

MASV recently sat down with veteran editor Michael Ruscio—who has cut more than 100 episodes of scripted drama including Carnival Row, Altered Carbon, House of Cards, Homeland, True Blood, and nearly 20 feature films, and has since been nominated for an Emmy for his work on episode 5, Judgment Day—to talk about the nuances of editing such a complex project.

Jump to section:

- How 3 Body Problem’s Editing Came Together

- ‘I Like Putting Together Puzzles’

- How Did You Come To Be on the Show, and Can You Describe the Cutting Process?

- How Did This Process Differ From Previous Projects You’ve Worked On?

- Can You Describe The Experience of Remote Video Editing?

- How Challenging Is It To Rework The Same Material Over Such a Long Period of Time?

- How Did You Deal With Difficult Scenes Involving VFX Set Pieces, Specific Blocking and Geography, and ADR Changes?

- Did You Go Into Production With a Solid Script, or Was It Very Fluid?

- How Did You Remotely Collaborate With Your Assistant Editor?

- What’s Your Process of Crafting a Scene, From Dailies To Your First Cut?

- What Else Do You Want To Achieve in Your Career as a Video Editor?

- That’s a Wrap…

How 3 Body Problem’s Editing Came Together

Weiland started working on the eight-episode series in the U.K. in November of 2021, and was joined by Smith in January of 2022—yet both wouldn’t finish on the project until March 2023.

As the complex workload and unlimited revisions of the show spiraled, L.A.-based Ruscio and Colorado’s Hauger were brought on in June 2022 to lend a hand.

For the most part, everyone worked remotely from their home edit suites:

- The L.A. team were connected to a server and worked from home during dailies and for a good portion of the cut.

- Each editor had a dedicated AVID computer in the post-production offices so they could remote control those machines via Jump Desktop, allowing the bins to update so the assistants could work on the most recent versions of sequences.

Ruscio and Hauger ultimately wouldn’t finish the project until early 2023. To say that editing 3 Body Problem was a mammoth effort would be an understatement!

‘I Like Putting Together Puzzles’

During our conversation with Michael, we spoke about:

- The unique challenges of editing 3 Body Problem, including managing notes from three remote producers.

- His approach to mentoring assistants in a remote world.

- Handling endless change requests and finding fresh creative approaches.

- Tips and tricks for rewriting scenes in the edit with additional dialogue recording (ADR).

- Strategies for mentoring assistant editors.

- Tactics for cutting a scene.

- The challenge of cutting in a foreign language.

If you’ve not seen 3 Body Problem yet, there are some minor spoilers ahead. It’s also worth noting that Michael’s episode 5, Judgement Day, is currently the highest-rated of the series on IMDB.

This interview has been lightly edited for length and clarity.

How Did You Come To Be on the Show, and Can You Describe the Cutting Process?

It was pretty atypical. Initially there were two editors in the U.K., Katie Weiland and Simon Smith, and they were meant to do all eight episodes. And then when it became clear that there was this huge sort of ‘Battle of the Bastards’ edit for episode five, they realized that they needed to go overseas and have somebody in Los Angeles do that episode. They brought on me to do episode 5 and then Anna Hauger did episode 6 to free up Simon and Katie because they still kept their rotation.

Ultimately, when Katie and Simon left in March 2023, Anna and I sort of adopted the series. I adopted 1, 2, 4, and 5, and she adopted 3, 6, 7, and 8. So we each ended up taking four episodes to completion.

My involvement was bizarre in the beginning. I had reached out to the post producer (Hameed Shaukat) to wish him a happy birthday, and we talked for 45 minutes, and then at the end of it, he asked, are you available?

I said yeah. And he says we have this 3 Body Problem, we’re in the middle of episode three and four, we’ve got episode five coming up. And so then I met with Minkie Spiro, the director. We had worked together a couple of times, and I knew Alexander Woo from True Blood. So we’d worked together, but I still needed to meet David Benioff and D. B. Weiss.

I met them, and it seemed like a good meeting. And then it just happened. I literally had to get an assistant over the weekend. I reached out to Josh Carley on Thursday, and then by Monday, we were working remotely.

There was some previs on the boat (scene) a little bit and they had shot a bit in Piccadilly Circus, London. And so we had those dailies, but everything else was just was coming in.

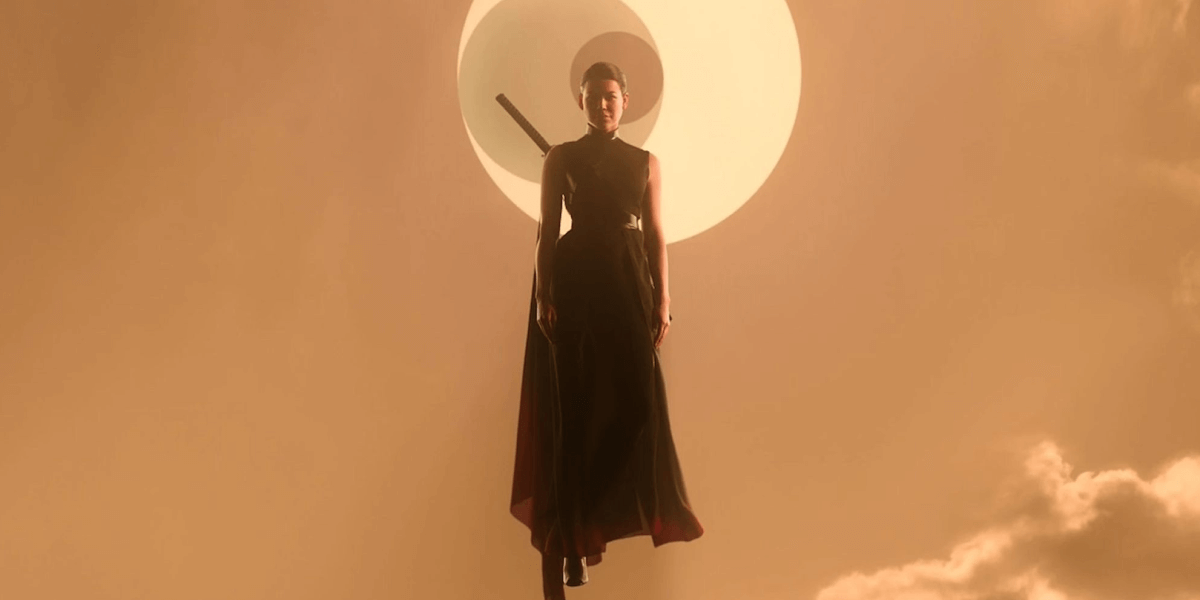

So we hit the ground running, introducing ourselves to the VFX team, working with them, and figuring out what the showrunners had in mind for the big ship sequence and the Sophon sequence.

It became really, really involved and I was on the show from June of ‘22 until January of ‘24. So a year and a half.

Level Up Your Post-Production Workflow

Use MASV for lightning-fast delivery of heavy media files.

How Did This Process Differ From Previous Projects You’ve Worked On?

It was very long. With a typical TV network show, you’ll have an eight-day shoot, your editor’s cut, the director’s cut, the producer’s cut, and the studio, and then sometimes you’re on the air a month and a half after you shoot.

In this case, we had the luxury of time. But it wasn’t like we were sitting on our hands. The work always expands to fill the time. We were constantly busy, constantly reworking it.

The way these particular producers work, the cuts are versioned in alphabetical order, so it would be cut A all the way to cut double-A. And the reason they do that is because they don’t necessarily want to say version two or version one, as if these are hierarchically better.

So they can sometimes say, “A month ago when we were in version F, there was a sequence that you did which I think would work better now, now that we’ve altered a lot of things around it in version K,” and so we lift that and put it in. That was a really unique experience working with them.

And they worked mostly with notes. There were three showrunners who would give us a comprehensive document, but sometimes in the translation things would get lost. Like, what is really the note behind the note? And whose note is it? And you could kind of tell after a while whose voice was whose.

It was strange being on something for this length of time, though, without being in person. We ultimately were in person a lot with VFX. We had a screening room where VFX would do their reviews every Wednesday, and so I would come in there for those reviews in person. Then, a lot of times, because there was an Avid there too, we would do sessions, or sometimes I would actually run the VFX session.

For example, with the Sophon sequence, we had ideas that we worked out with editorial that we had to translate to VFX. That was kind of a push-me-pull-you relationship because sometimes I would be leading and sometimes I’d be following, and it varied based upon the needs of the particular sequence or set of shots. I was always in the VFX reviews for the first five episodes. So we’d start to understand the length of time the process would be. And I just immersed myself in it as much as I could to understand the storytelling idea with the visual effect component, as well as where the story had come from and where it was going.

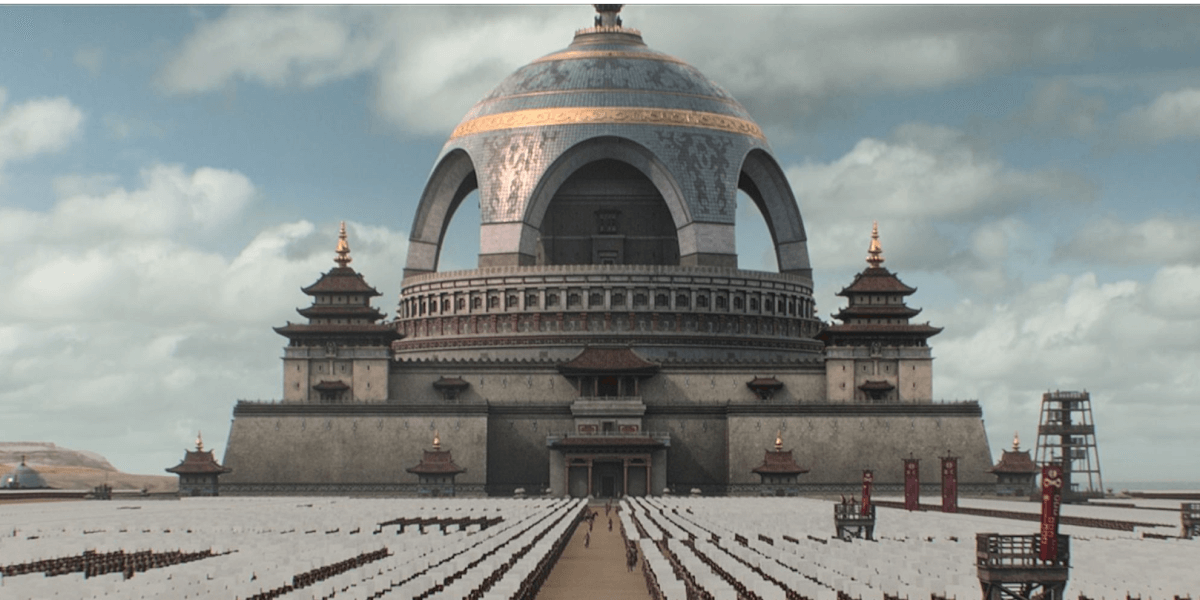

Episode five, Judgment Day, is a culmination of the first four episodes. And it’s almost like a finale in the middle of the season. Because after episode five the nature of the storytelling changes a little bit. And it goes into a different spin. And episode five is the zenith of the first five.

SOURCE: RadioTimes

Can You Describe The Experience of Remote Video Editing?

I think working remotely in the editor’s cut stage is pretty successful because I’m in dailies, I can talk to my assistant, I can put a locator on a sequence asking her to do a certain kind of fleshing out of a sound design, and I’m on my own anyway.

Where I think it’s especially difficult is in the director’s cut portion of either a film or in television. I did a film called Raymond and Ray that Rodrigo Garcia directed. I did the first cut at home and then we were in offices working together, but then they shut us out of the offices because of COVID.

We used Evercast. We also had a shorthand, because we’ve known each other a long time and we had worked in person before. But one thing I like about Evercast is that I can add my assistants to the stream so they can witness the dynamic between director and editor. Because they can often miss out on that (in a remote workflow).

Those director’s cut days are very intense. The directors take it very seriously because they have a limited amount of time. So I try to include the assistants in whatever I can. And so the way I’ve designed my remote situation is to include them in the Evercast call, and then they can do their own work and they can sort of chime in or just listen in.

It’s a way, I think, for people to grow and learn. And that’s something that since remote editing is happening more and more often, there’s a concern a lot will be missed. That we don’t have the camaraderie with other editors.

Easily Transfer RAW Files For Video Editing

MASV has no limits on file package sizes and handles individual files of up to 15TB.

How Challenging Is It To Rework The Same Material Over Such a Long Period of Time?

I like putting together puzzles, and it’s always fascinating to see just how elastic material can be. And you know, sometimes you’re in a corner, but it’s like an escape room.

(Sometimes) I got a new note and I thought I’d already gone through this maze, and figured out a way out, but now we’re saying, “We’re changing where the window is. So you need to find a way to open that window and still have the light coming in from the direction it was coming in from.”

But I enjoy the process of challenging myself to be open to it. As an editor, you’re an audience, and part of the skill set is having a clean slate, just wiping it clean and looking at it fresh.

Sometimes I put together a sequence pretty quickly, then send it to my assistant, and then not look at it for a while. And then maybe when I get a scene that’s after it or before it, I’ll re-examine it.

It’s a lesson in detachment, really. A lot of times when people are starting out they feel like they’ve made a great scene, they’ve made perfect choices and then they’re bristling a little bit because you’re changing something that they thought was so good.

And then as time goes on, it’s not like you’re not invested in it—you’re kind of weirdly more invested in it. But at the same time, you detach from it because you’re sort of invested in the whole process versus just the initial idea. And I love how ideas change.

One thing that’s fascinating as far as actors and performances, is that oftentimes, way down the road, the producers will say, “Is there a take where she’s more this, or where she has this kind of thing, or she seems more scientific or more believable as a physicist?”

And initially, you think: ‘Wow, she seemed like really passionate in take six’ after the director had worked with her. But then you realize, well, if she was really a good physicist, it would just roll off the tongue, and it wouldn’t have that kind of an emotional investment. So as the process goes on, you sort of see, ‘Wait a minute, maybe I’ll look at those other takes again. Maybe there’s something in there that I missed the first time.’

As time evolves, so do your ideas. I find it really fascinating. It’s a circus of sorts. Sometimes you’re on a tightrope and sometimes you’re just on a trapeze.

How Did You Deal With Difficult Scenes Involving VFX Set Pieces, Specific Blocking and Geography, and ADR Changes?

Sometimes there were AniMattes, which is hard because they were both in each other’s shots (re: The episode five house scene featuring both female leads). Eiza (Gonzales), especially, was very animated physically. So it would be an AniMatte and the freeze would be at 25% speed so that her head wouldn’t necessarily move down or you couldn’t tell that she was picking up a pencil or the newspaper. That happened a couple of times.

It’s easy to just think, ‘Okay, we’ll just go to close-ups and this won’t be a problem.’ But then it doesn’t feel organic at all. So I think that was why it was difficult in retrospect, because I wanted to keep a flow that had a nice shape to it. Sometimes you can have close-up overuse in movies, and especially in television, and I wanted to preserve the geography of the space, as well as the two of them together in their emotional dynamic, and save the closer pieces.

SOURCE: The Hollywood Reporter

Even with the sitting down on the chair (part of the scene) we were taking out dialogue when she was moving, and then adding new dialogue after she sat down off-camera, and still making it fit.

That’s a tricky thing about ADR: when you have lines added in a very small space, and a very small physical space, and a very small space before the other actor’s gonna start their line. You can add as much head to a shot as you have available, but sometimes you butt up against the end of their line that they just said, where the new line’s going in.

So sometimes I’d do speed ramps in that as well. In another scene with Wade and Da Shi, when they’re figuring out what they’re gonna do, how they’re gonna get the hard drive, we added a lot of ADR lines in that, too.

The pattern of editing is then such that you have a lot of off-camera dialogue in the beginning of the scene so that you’re setting people up to expect that, so if a new line is put in here, it is still part of the same structure and rhythm that the editor provided us to start with. So it’s disguised a little bit better.

Did You Go Into Production With a Solid Script, or Was It Very Fluid?

I think it started solid, but as it moved on, and especially I think with episode five, they realized that there were three big set pieces that happened later in the episode.

Initially, Scene 17 was the scene where we’re on the (boat) deck and Mike Evans is talking to Felix. But there are 16 scenes to get through, which is half an hour, so how do you keep that as taut as possible? Letting people know that there is gonna be excitement, but we needed to keep that thread alive. So in the process of doing that some things were simplified, and that was why there were lines that were added.

SOURCE: Polygon

And also, once we knew we were going to do additional photography, then it kind of became, ‘OK, well, what are we really, really going to do?’ Let’s hone in. And even then, for example with the Sophon sequence, where Jin and Wade are looking up to green screen and Sophon is explaining about protons and unfolding and splitting and etching in the sky, my assistant Josh Carley and his wife Jamie would do temp lines for us because we were constantly changing her lines before we did the additional photography.

And then even after that, we were changing it again. Do we want to have this be more in-the-game sky versus on her face? Or she’s going to start to say something and then it will move off to a different shot. I had like crazy markers at some point saying, “VFX and sound note, non-sync on-camera dialogue.”

How Did You Remotely Collaborate With Your Assistant Editor?

I think a big part of that—and I’m on a project now, so I’m working with a new assistant, Araceli Rodríguez Vargas—the job of being an assistant editor is so vast, and you’re right, there’s not much time. So them having the time to cut a scene, that is a luxury that isn’t possible so much anymore because it takes a while to craft that scene and then we’re giving notes back and forth.

So what I do is I’ll ask, “Can you open this bin? Can you watch this shot?” Then I’m asking questions like, “Are we supposed to think that he’s hearing that in this shot? Or do you feel like it tracks that she doesn’t care about what he just said and there’s a private moment where she does?”

And so you both challenge the ideas together, based upon the footage before you even start cutting. And other times it’s just helpful to clarify things and figure it out together. I’m talking it over with the assistant and then they’ll say, “Well, what if you did this?” Or “That’s how I saw it too.”

Because a lot of editing is—when you see dailies and it’s not what you thought it was going to be when you read it—a lot of editing is getting out of your own way. You have to go through these stages of grief, really, before you accept, okay, this is the footage I have.

I’ve found I have to really wrestle with it before I can sit down to edit. And then when I do sit down I can do it really fast but I have to divest myself of all these other preconceived notions, and so working with my assistant in that way really helps.

And I think it helps them too. And it’s funny, I said to Araceli, point blank, I said: “You’re so busy, and I want to mentor you and help you to become an editor, but there’s no time.”

But then she said, “You know what? The way we’re doing it helps me more. Because it makes me think. It’s not just cutting a scene by myself or whatever else, this process makes me actually think about how to approach a scene.”

I’m glad that she said that because finding creative ways to keep people engaged is important for the future of the craft.

The Best Large File Transfer Tool for Video Editors

Share uncompressed large media files with MASV.

What’s Your Process of Crafting a Scene, From Dailies To Your First Cut?

Viewing material at least a couple times, and I do follow a lined script but also, at first, understanding ‘Okay, setup K is really the beginning and setup 601 and 601A are actually later on in the scene,’ so at first I just try to figure out the math of it.

I have my assistant craft the bins that way, so the clips are more or less sequential within it and then evaluate: What is the key moment? Norman Hollyn, who was a great teacher and editor, called it the lean forward moment: What is that moment in the scene we’re building up to?

This is critical, and sometimes that means this is where I have a really tight shot, and sometimes it’s a wide shot, and people are sometimes allergic to this.

SOURCE: Vox

But I find it really effective where suddenly you’re in a really wide shot, which tells you a lot about someone’s isolation or the space they’re in or how it’s not as private as you thought it was. And that becomes almost a breathtaking moment. And it’s tricky using that because a lot of times people have a bias, producers and directors have a bias that we’re already in the close-ups.

And so finding a way to utilize those wides or close-ups effectively where they’re still telling the story is something I look to a lot of times, as well as when do I really hone in on that moment.

And sometimes there will be a specifically designed shot for a key moment in the scene, but then you realize, wow, everything around that doesn’t really flow into that shot judiciously.

So I’ve got to either not use that shot, or maybe just cut into it or something. Or I’m gonna have another version at the ready because I know the director’s gonna wanna see this shot.

It also varies based upon the scene. Many times, because the dailies you get are not necessarily shot in sequence, you’ll do a scene and you’ll think you’ve got it lit, and then you get the scenes around it and you say, “Oh, shoot, the director used that dolly open both times.” So I’ve got to make a choice—which scene am I going to use that with?

Or you have two scenes that are back to back, or three scenes, and you think it should actually be one big scene as opposed to three individual scenes. How does that work with the audience? Where are they tuning in? Where are they tuning out?

What Else Do You Want To Achieve in Your Career as a Video Editor?

Well, right now I’m doing a project that is partially in Korean. And people ask me, “Do you have a translator?” And I say, “Well, yeah, but sometimes they go off-script. And we’ll send a cut to our post supervisor in Korea to make sure that we’ve got it right, as far as the language.”

What’s really fascinating is I’m really having to watch the dailies very seriously and consistently to understand it all. It’s almost like being on Rosetta Stone, where I can tell that this is actually a better performance but there’s a noisy track here, so is there another take that I can use? In the U.S. I would just know I can take that syllable, because I know it’s a similar tonality and it’s the same three syllables, and I can put them into this sentence and it flows.

Because it’s in Korean, I’m listening to it intently, I’m listening and re-listening. Okay, this sounds different but it’s actually just because it’s better acting. Or they’re more into character in the later take for some reason. But then I really want to have this wider shot. So can I put those words in there? Is it going to fit? And is it going to be the same? Which is not completely an answer to your question, but it’s fascinating having that sonic challenge of another language. So I guess I’m doing that right now.

That’s a Wrap…

We’d like to thank Michael Ruscio for educating us on the finer points of cutting such a complex project, his remote collaboration with assistant editors, handling endless change requests, and tips and tricks for re-writing scenes in the edit with ADR.

Video editing with RAW footage received as dailies (or rushes) each day from the field or set means editors need tools able to handle such heavy files before they’re transcoded into more edit-friendly formats such as ProRes, ArriRaw, H.265, or MPEG-2. Assistant video editors must receive, ingest, and organize these large files quickly and reliably. To safely and effectively transfer large digital media files to and from home editing suites, facilities, or to a cloud storage bucket, video editors can use MASV file transfer.

MASV browser-based file transfer is the fastest, most reliable solution for transferring extremely large files from the set or elsewhere for in-house or remote production teams.

Sign up today for MASV and receive 20 GB for free towards your next transfer. While MASV can’t help you rewrite scenes in the middle of the edit, we can certainly improve your file transfer process.

Large File Transfer for Post-Production Teams

Fast, reliable transfer for in-house and remote post-production teams.